This interview is part of a creative exchange between Cultural ReProducers and the artist-run gallery CommaSpace in Singapore. It began during a residency where connecting with fellow artists meant meeting online because of the pandemic. Given these circumstances it felt especially lucky to meet Faye in person to connect over our mutual creative interests, and we followed up remotely once I returned to the United States. (Christa Donner for Cultural ReProducers)

Cultural ReProducers: How old is your child now? How would you describe him?

Faye Lim: He is going on seven. It’s funny - recently my word for describing him has been “perfect.” I’d been thinking about it, and this word just kept coming up. Clearly not everything goes according to plan, but all the areas that he's growing in, learning in, figuring out, struggling - everything just feels like it makes perfect sense with who he is.

CR: What has changed in your creative process after becoming a parent, and what has stayed the same?

Faye: I think what's been constant is my practice in movement improvisation, as well as studying and experiencing what freedom and the sense of liberation are like. I’ve always been quite topsy turvy in the way I choreograph and make dances, and having a child has enriched that approach and the sensation of disorienting and orienting again.

I experience dance differently now, after becoming a parent. Time and space and energy-wise, certain restrictions closing in on me. But moving around with him, improvising with him helped me to…play, I suppose, with that feeling of time and space closing in. I've been getting really a lot more curious and paying a lot more attention to how children and different caregivers move and work with their bodies. I mean, when I think about movement improvisation, dance improvisation - I also think about the autonomy and self-determination there and then. Like, how do children experience that? How do they experience their bodily autonomy around their caregiver - around adults, in different settings?

|

| image by Kavitha Krishnan, courtesy of Rolypoly Family |

Faye: My practice now includes working with children in a committed way. And also because of the attention I've put on advocating for artists with caregiving responsibilities [through Parenting Artists SG], I have started to work with artists I didn't used to have interactions with. Some of them have become very important and supportive peers for me, and I hope me for them also.

I think some folks think of me as only working with children. I'm happy about that work, but I also have mixed feelings about that. I don't think this is the case across artistic communities and families - but there is definitely that association of “oh yeah, she is the artist who works with children and cares about caregiving.” (laughter) At the same time it's also quite thrilling to be able to bring these aspects into the fold of our dialogues as artists, and to be available to other parties who care about this model. Within this community, there’s this artist – they and I have been practicing contact improvisation together, and organizing events here in Singapore with other folks as well. But it was great when they also became a parent, and I was dancing with them when they were pregnant. Just to be in that space of overlap – of our movement practice, our changing bodies, our changing identities and of having this other being tag along and be around us. I was one of the first among my friends who was practicing and became a parent. Here in Singapore, I didn't have many parenting dance artists as predecessors when I had just given birth. There are a few dance artists I work with closely, who have either just given birth or are about to. I feel like a community of support is more possible now.

CR: Being a parent in the performing arts poses specific challenges: there are so many components that you have to physically show up for – rehearsals and performances coordinated with many other people. Building that community seems crucial. Could you talk a bit about the group you recently launched, Parenting Artists SG?

Faye: Yeah, so we had some informal meetups in 2020. I wasn't actually all that keen on starting another Facebook group – but out of the first meeting we had, just at the start of the pandemic in Singapore, there were suggestions from the group to start something online, where people could gather. It was February 24 2020, just as Covid-19 cases were increasing here, and I specifically remember, we were on the edge of our seats - like “Can we do this? How can we meet up safely? Do we do this online?” We did temperature checking and signing in (for contact tracing), and it was hybrid, so the three or four artists who didn't feel well, they had their own discussion group online, and the rest of us met in person. The people who came were not only from the performing arts, but you are right to say there are challenges unique to performing artists.

CR: How did that initial event come about? What was the impetus to get it started?

Faye: Well, when my son was quite young I gathered a very small group of artists who wanted to discuss parenting, inspired by an event at Movement Research in NYC. Four of us met to chat about what our experiences had been like, as working artists and as arts audiences (3 parents, 1 artist who was not a parent yet and became one a few years later). Two years later another small group got together, including two producers. In the meantime, I was looking around online, researching how other artists were talking about being parents. Cultural Reproducers is a resource I went to a lot, and a couple of others, like Mothers Who Make. One of my producer friends posted something about a residency that was specifically supporting parenting artists and mentioned it seemed like a positive direction. And then another friend who is not a parent – who was advocating for more visibility and more support - posted that she wanted to do more. So I approached the both of them - it was me and these two friends who are not parents, but who care about this.

That set the tone for how things came together. There are folks who are active in the group who are not parents, and I really appreciate their attention, their care, their time in organizing some of this together in sharing resources. One of them combed through the internet to locate all the relevant government and arts policies, and created a resource document. A lot of these things I wouldn't have been able to cobble together if not for these folks. One of them is a producer who is an organizer with a group of arts producers here called Producers SG. It’s quite deliberate that there's that partnership with Producers SG, because there's the push for artists to work in teams - we want to not handle everything on our own, and a lot of the times the producers are the folks who are helping to gather the resources. They gather the funds for the work, and they are the ones who then help to put the provisions that are needed – like childcare- into the budget sheets, into the application forms, into the negotiations with funders and such.

CR: I don't know if it's a performing arts thing or if it's a Singapore thing, but could you just briefly explain what you mean by a producer here? It is not something that I had heard about for smaller groups of artists in the United States, but it seems quite common here.

Faye: Oh, my goodness yeah. It’s funny because you’re called Cultural ReProducers, and like, how are we using those terms differently? So first a disclaimer: I think different producers work in different ways for different projects. The producer typically helps make the project happen - the person who pulls the creative team together - whatever technical or administrative needs, and they may put in the infrastructure for the timeline, the fundraising, keeping the project on track in terms of division of labor and such. So they help make it happen, and take that load off the artists. Just this past year, during the worst of the pandemic here, I got to work on my first project fully produced by an independent producer.

Having producers that understand what it's like is very helpful. One of the producers went off to a festival in Europe where they were talking a lot about the visibility of work by women artists. He came back with an understanding of what to look out for to produce in a way that's more inclusive. So I feel like these things are happening in parallel.

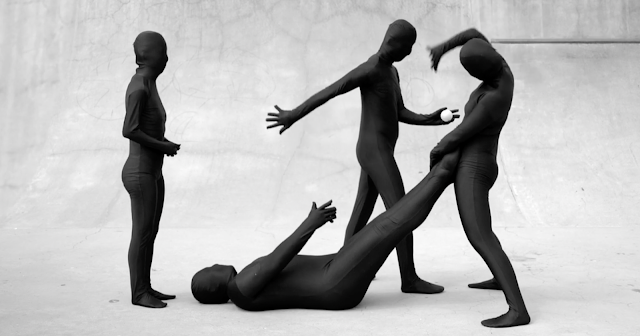

|

| a still from the film "Beautiful Fields Beyond Me," (currently in development). image by Faye Lim |

Faye: Culturally, there are quite specific expectations of how children should behave, and that puts these expectations on the parent as well. And art spaces, as you know… as progressive as we imagine them, sometimes are not necessarily progressive. That whole “children should be seen and not heard” thing. The arts community here is many communities. It’s really diverse. I think there are some other communities within the arts that are comfortable sharing space with children, but I don’t think in the contemporary dance community, that we can assume a familiarity with sharing space with children. Either that, or children tend to be objectified or exoticised - they are interesting and valuable to some artists insofar as they further the artists’ vision and artistic goals.

As someone who parents a child and advocates for children’s rights, it is quite challenging being in some of these spaces - but that has been an opportunity of growth for me. Practising compassion and empathy for my colleagues, collaborators, partners and myself hasn’t always been easy but has certainly paid off. The frank discussions and negotiations make room for us to challenge assumptions and can be generative for the working relationship.

I think another thing is also the concept of caregiving – is it a community or a society responsibility, or is it on the individuals. he concept of caregiving, when confronted in the workplace, feels very much like an individual's responsibility. I have heard laments about how other colleagues/collaborators have to take on extra workload when a parent takes childcare leave. The idea here is - your child, your problem. Whereas in some arts communities I am fortunate to work in, caregiving is viewed as part and parcel of work life - whether it is the care of a child, an elderly family member, or a colleague who needs extended medical care. I much prefer the notion that caregiving is something we look at collectively, so as to invest in our collective health and future. My friend had started up this informal performance space called "Make It / Share It," and that was also the time when I was thinking about how to thrive as a parenting artist. I talked to her about it and she said that in Sweden, children are anywhere and everywhere - they are present in arts spaces. So she created this open stage performance platform and added guidelines like “children are welcome.” She didn't call it a “family” space. Her guidelines were along the lines of “If you want to perform here, do expect that you might hear some sounds from children - don’t get grumpy about it.” I performed there, but I also brought my son to shows. I have friends who make movement-based improvisational performances, and it was great to have this space where my son could join in, and they were so able to incorporate his sounds and his movement and his story-making into their show. That's the kind of risk taking, the kind of disruption and improvisation that I’m interested in when I make art. It doesn't have to come from a child, but how often do we get another adult audience members disrupting our show, much less in Singapore? (laughter) That’s the energy that I am completely excited by - to have a space where my son could be himself and the artists could be themselves… it was really perfect.

CR: I’m curious what projects you’re thinking about these days, or longer term, once your child is older.

Faye:

I have different strands of creative energies and goals and visions,

and they tend to overlap, intersect, and diverge. Alongside what I’m

making as a dance artist, I've been looking for avenues where I can have

more conversations and intersections between art and public health,

specifically for children. I’ve been trying to lay down some foundation

to work at that intersection, whether it's as an artist, as an

organizer, as a consultant. And then, alongside that, always my movement

practice in contact improvisation. That’s like a stream that just flows

for me, on and on and on. I imagine that will continue, and I’ll have

different points of discovery along the way with my movement practice,

and I don't necessarily have a plan for that.

| |

| Faye Lim dancing in "Telescopic Dreams," image by Finbarr Fallon |