Cultural ReProducers: Could you describe your daughter in your own words? Age, name, general temperament…

Nīa MacKnight: Elle is twelve, about to be thirteen. She’s very inquisitive, bold, a bit… mischievous. She has a lot of passion. She loves everything fiercely, whether it be animals, people… she has so much love for the world.

Cultural ReProducers: So when she was born, what kinds of expectations did you have about being an artist who's also a parent? And how did that square with the reality of it for you?

Nīa MacKnight: So I had my daughter when I was 21, and being a single parent at that time I felt I didn't have the energy to create anymore. Just trying to keep up with everything… I was depleted. I didn't see a place for me in the world of photography, specifically photojournalism. I gave so much of my physical energy working jobs that weren't creative, getting a degree in psychology - I was really focused on understanding my role beyond the arts.

When I started navigating the art world I noticed this lack of dialogue that included support for artists that are also caretakers. There’s this expectation that you're on your own. That individualism can be alienating. I’ve really had to think about how I'm supporting my work, how to carve that space for myself if it doesn't exist elsewhere. So I've had to take jobs outside of creative labor. And I've learned to really draw inspiration from daily life.

|

| Hand of Light, Nīa MacKnight |

When my daughter was maybe three or four, I have this very visceral memory: we were at our apartment,

around that magical hour where the light is filtering through everything – a little bit softer and golden. It had been a long day. I picked my daughter up from preschool, and we're finally home making our dinner. I look over and I see this very direct ray of light piercing through the curtain. And my daughter noticed it and put out her hands, and then I see in that moment, “what a beautifully composed image.” I grabbed my camera, worked really quickly, and was able to capture that moment. That particular memory is really a catalyst for the type of work I do. It reminded me that although there may not be space for you right now, continue to make work. Maybe there will be a space or a time where this work means something to someone else, but for now it means a lot to you.

I don’t agree with this idea that you have to give up an art practice when you have a child. I saw in that moment that this everyday experience – my daughter’s really the source of inspiration and energy that fuels my work as an artist. How could I separate those worlds? I'm always thinking of how psychology and art intersect. I don't work as a therapist, but as a teacher, you know, you work many roles. I always think of art as a form of transformation and healing. What else could it be?

Cultural ReProducers: I love that, and I totally agree. I think that for any parent, there's always this question of what kind of world our children are growing up in -- what we hope for the future. Does this transformative practice in your artmaking connect to that?

Nīa MacKnight: Yeah, thank you. I think that through experiences of caregiving - whether you're a parent, or a teacher, or taking care of your own parents - you’re giving your energy and often that makes you feel depleted. Right? So it becomes more and more important to hold space for yourself while you are caregiving for others. That could look like painting, that could look like going outside to take photos. That could just be staring outside the window and reflecting on a concept that is evolving, or a memory from years ago. Photography is this tool to turn that into a material form. That’s something that as a society we don't hold enough space to talk about: health and wellness… we’re not designed to produce at an industrial rate. If we're creating this life form, it’s a story that takes years and years to get right.

That’s where I hope my daughter, that the times she's navigating are different. Maybe we'll get to a place where we're evolved to hold more space for parents, in particular mothers, to heal. Financial support to navigate working and caretaking, and the way we treat elders. I hope that evolves by the time she's older. But you know, I think it's still really important for her to always hold space for herself.

|

| Future Ancestor, Nīa MacKnight |

The medium of photography is immediate, and directly engaging with the world. I hope that my daughter, and my students … youth, that they continue to utilize this tool to engage with the environment. Engage with their own family histories. To look inward. To find your role in the outside world. How to expand on time as a cycle. According to traditional teachings, time is not linear. We play a critical role in the cycle of life. Every material object we create, that's a story. Each story has its own life force. And it keeps getting shared and taking on new forms, new interpretations. As storytellers, it’s a huge responsibility to make sure that that story is ready to be shared with the next person, and the next person after that, so the story is always living in time.

Cultural ReProducers: Who have been your role models in artist-parenting / parent-artisting?

Nīa MacKnight: I feel very fortunate that I grew up in a house where art was very much part of daily life. I think of my own mother. You know, our situations were different, but - despite having multiple children to take care of, and taking care of her parents - she still carved out time to make art. She sewed these little dolls and would often sell them at local fairs or boutiques, and that evolved into painting and drawing. Although she wasn't commercially successful then, she still carved out time to create. Now she's much more well-known, but I witnessed her struggles, and how she used art to carve out more spaces to be seen

|

| Womb, Nīa MacKnight |

Living here… LA is so sprawling and big - sometimes that can feel isolating. Being a really young mom, I thought I was the only one navigating all that. But out here in the South Bay area I've come to meet a lot of people that, although at first we didn't share that we had children, our art started this dialogue. As my daughter got older I met a lot of other artists: Jenn Graves comes to mind, Carrie Dietz, JaNae Collins … those are just a few that come to mind. All working artists - whether they’re printmakers, painters, or actors - they’re playing an active role in their children's lives, in a very competitive urban environment such as Los Angeles.

Cultural ReProducers: Your work is also tied to family in a more expansive way – connecting you to traditions and stories of your ancestors. Could you say more about how that has shaped your photography?

Nīa MacKnight: Well, I come from mixed ancestry: I'm Lakhóta, Anishinaabe and Scottish, so both indigenous and settler histories. My childhood was very multiracial and also intertribal. All these different sources of knowledge really permeated everything. So within my work I'm always drawn to the contrast of energies: reflecting on the role of humanity within urban environments, which are so layered. Here in LA, I'm a guest on Tongva territory. These aren't my traditional homelands. I'm always drawn to people in the community that exemplify duality. Their stories truly show that these energies can coexist.

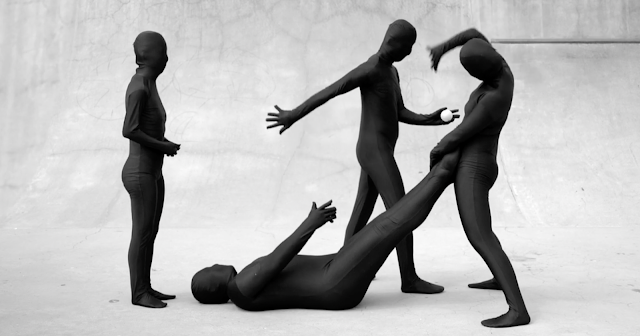

|

| Child of Industry, Nīa MacKnight |

Los Angeles can often seem very post-apocalyptic. There’s that relationship with the oil industry. My family lives right by a refinery. Cars everywhere, concrete. Thinking about assimilation, and in particular, my family's role within that in history, in the United States. My work really examines this duality between two worlds: the industrial and the natural; The material and the spiritual. I'm drawing from ancestral memories, and my role as both a witness and a participant, trying to harvest intimate moments in a landscape of colonial violence.

Right now I’m showing a specific series of photographs and a site-specific installation titled “How do your ancestors find you if you don't have a name?” I was thinking about last names, in this modern world, as a way of really carrying on a family's legacy. I thought also about my own government name and I was confronting feelings of shame, because there there are traditional Lakhóta ceremonies where people are given a name… as a way for your ancestors to meet you beyond the physical world. My aunt, who lives out on Standing Rock, shared with me that a lot of people don't have these names. It's not as common anymore.

Lakhóta society is very matriarchal. As I was digging and thinking about my relatives, I recognized this pattern of women not taking on their partner's name. Women have their own essence. Their role in society was very different than it is today. I really wanted to highlight how colonization, but also assimilation, is reflected in names. So really questioning, what is a name? I believe that your ancestors can find you no matter where you are, whatever name you have. They are always there with you.